Digital technology promises nothing less than a complete transformation of the way in which we look at art. It can produce images of such high resolution that brushstrokes and craquelure – details that not so long ago would have been the privileged view of specialists equipped with lights and magnifying glasses – can now be browsed through, by anyone, free of charge. And paintings once lost in the dusty corners of museums have been brought into the public domain, via digital resources such as Art UK and Google Arts & Culture.

The National Gallery’s recent exhibition ‘Monet & Architecture’ included a collaboration with Google Arts & Culture, making editorial content and high-resolution reproductions available online, and including an installation in the gallery that allowed visitors to look at Google Earth images of the locations painted by Monet in the late 19th century. The main aim of such collaborations is to make works of art accessible, but digital interventions inevitably also affect the way works of art are experienced.

The idea that our experience of the artworks is changing, however, is downplayed by Marzia Niccolai, of Google Arts & Culture, who emphasises that providing museums with the technology to realise such projects is motivated by altruism, and is intended to draw people into museums. Digital resources broaden the global audience for art by making it more readily available, and stimulate curiosity about the objects themselves. Niccolai says, ‘Nothing can replace the physical experience. It’s not just about the artwork, it’s about the experience, it’s about the place.’

Even so, art exhibitions are subject to the same pressures as any other commercial enterprise and, in an increasingly competitive market, novel installations and a comprehensive online element provide marketing departments with extra leverage. Chris Michaels, director of digital at the National Gallery, concedes that digital projects can drive visitor numbers, but argues that ‘what we’re trying to do is to tell stories that more broadly enhance the public understanding of the artist and their work’.

The developers of new digital tools are more upfront about creating fundamental changes to the way in which academic research is carried out. John Resig, who is responsible for developing image-recognition software for PHAROS, explains that Image Similarity Analysis (ISA), which uses machine learning to match similar or identical images, can overcome many of the limitations of searches driven by metadata, which can vary in quality and content between institutions. He explains that, ‘If all metadata associated with an image is ignored, and only the contents of the image were analysed, it becomes possible to find interesting image matches that were likely undiscoverable using raw human power.’

In order to test the potential of ISA, Resig has analysed the Frick’s photographs of Italian paintings by anonymous artists by customising TinEye’s MatchEngine, a commercially available image-recognition service. He found that it not only confirmed some established relationships between images, but also suggested new ones. ISA, Resig says, is capable of identifying cataloguing errors, copies of the same object, details of the same object, and images of the same artwork before and after restoration. ‘Images rarely lie,’ he explains. ‘When they do, there’s likely something interesting happening that would be a good area for further research.’

While the PHAROS project makes use of existing software, the Digital Humanities Laboratory (DHLAB) at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne is working on a project called Replica, the first search engine designed specifically to sift through visual information. The first phase in its construction is the digitisation of the photo library of the Fondazione Giorgio Cini in Venice, which contains around one million photographs. Once this has been achieved, it is hoped that the search engine will serve as a blueprint for other institutions wishing to preserve and share material in this way.

For scholars, museum staff and the art trade, making the results of high-resolution photography available online has clear practical benefits. Even so, it provokes a cautious response from some, and as a spokesperson in the press department of Christie’s tells me: ‘Technology in the area of digital imaging has made a great difference across our business. But this form of attribution is only one of a handful of ways we gather information about a work, including using a back light, documentation, academic research, pigment dating etc. All this, together with the opinion of our departmental specialists who have many years of combined experience, creates a “picture” of a work to provide the reassurance we require.’

Leonardo expert Professor Martin Kemp is similarly circumspect: ‘Very high-resolution images and multi-spectral scanning are transforming our resources for looking at art. We can see things that elude us in the galleries. However, they do not substitute for the physicality of the actual object, and they can make a work painted with minute precision look as it was handled in a very painterly manner.’

As visual resources have migrated online, the disappearance of slide libraries, once the backbone of departments of art history in universities, suggests change that is not only rapid, but total. But if the study and display of art is changing, the changes are still dependent on photography, a medium that has played a central role in art history since it was invented. As the French art historian and politician André Malraux put it in his essay ‘Le Musée Imaginaire’ (1947), art history is ‘the history of that which can be photographed’.

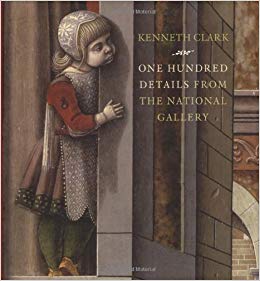

In their three-decade-long correspondence, Kenneth Clark and Bernard Berenson routinely shared photographs as a means of discussing works of art, and Berenson’s vast archive was essential to his connoisseurial endeavours. As director of the National Gallery from 1934–45, Clark set about photographing the gallery’s collection. A selection of these images appeared in his book One Hundred Details from Pictures in the National Gallery (1938), which set new standards of photographic reproduction. Just as Google’s Arts & Culture app rests on the broad appeal of high-resolution reproductions, so Clark recognised the value of good photographs beyond professional circles, describing his commentaries as ‘the kind of conversation which two people fond of painting might have while going round the National Gallery’.

In their three-decade-long correspondence, Kenneth Clark and Bernard Berenson routinely shared photographs as a means of discussing works of art, and Berenson’s vast archive was essential to his connoisseurial endeavours. As director of the National Gallery from 1934–45, Clark set about photographing the gallery’s collection. A selection of these images appeared in his book One Hundred Details from Pictures in the National Gallery (1938), which set new standards of photographic reproduction. Just as Google’s Arts & Culture app rests on the broad appeal of high-resolution reproductions, so Clark recognised the value of good photographs beyond professional circles, describing his commentaries as ‘the kind of conversation which two people fond of painting might have while going round the National Gallery’.

In his preface to a new edition of One Hundred Details, published in 2008, Nicholas Penny writes that the book was able to ‘transcend some of the barriers inevitable in the organisation of the Gallery itself’, an aim consistent with today’s online resources. Similarly, Google’s recent collaboration with the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in presenting a virtual exhibition of the works of Pieter Bruegel the Elder is to a large extent a new way of achieving ambitions that began in the pre-digital age.

In October, the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna opens a major Bruegel exhibition, although until now the extreme fragility of Bruegel’s panels has precluded most of them from travelling. The solution the Royal Museums of Fine Arts found in Brussels in 1969, the 400th anniversary of the painter’s death, was to conceive an exhibition that reunited all of Bruegel’s works – through an installation of actual-size black-and-white photographs. Nearly 50 years later, the museum has turned to virtual reality, in addition to its online exhibtion, creating an immersive experience with its ‘Bruegel Box’. The Fall of the Rebel Angels (1562) is the first in a series of the painter’s best-known works to receive this treatment. It is available online and can be experienced using Google Cardboard and a smartphone.

If One Hundred Details anticipated some of the current applications of high-resolution photography, yet another former director of the National Gallery, Neil MacGregor, discussed the implications of making such images available. In 1990 he observed that since the first edition of Clark’s book in 1938, many of the featured works had been cleaned, which makes it a document of record.

MacGregor writes: ‘As they are shown in this [1990] edition, Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne and Holbein’s Christina of Denmark are different in critical respects from the paintings Clark discussed. The reader who can compare the earlier edition with this one will decide how much is gain, how much loss.’ According to Michael Daley, director of ArtWatch UK, it is for this reason – for fear of inviting criticism – that museums can sometimes be reluctant to supply photographs taken before and after restoration work. Daley concedes, however, that the National Gallery has allowed him full and helpful access to its records.

For Daley, the possibility of making photo comparisons is ‘the greatest gift imaginable to connoisseurship’. He feels that they can, in some cases, obviate the need to see the work itself. ‘The idea that you can only make a judgement about a work of art by seeing the original object is total rot. Mostly the photo is sufficient. It might be the case that at some super-refined level, in some really close issue of connoisseurship, it would be necessary to see the thing and it’s always desirable to see it in the flesh – but with restorations it is only possible to see pre-restored states in photographs.’

The Replica scanner at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini in Venice. Photo: Matteo De Fina; courtesy Fondazione Giorgio Cini

Whatever the many advantages of digitisation, it is a time-consuming process. The Replica scanner being used at the Cini Library has been specially designed for the project by Factum Arte, which describes it as a ‘rapid photographic capture system’. The digitisation project, which began in March 2016, is expected to be completed this autumn. By comparison, the Warburg Institute in London, which forms part of the PHAROS consortium, holds around 400,000 photographs, which it began to digitise in 2010. It estimates that so far around 15 per cent of its collection is available online.

Aside from the practical difficulties of digitisation, not everyone is convinced that machine vision can match, still less surpass, the eye of a trained researcher. The art historian Richard Emerson welcomes the prospect of photo libraries being able to share their collections. But he adds as a caution: ‘We may still be some way off the day when a search engine can identify that a fragment of romanesque carving built into a wall in a parish church and photographed in the 1930s, together with a clutter of notices and flower arrangements, is possibly by the school of carvers responsible for a now very weathered romanesque doorway 150 miles away and in another country. Such a link can be made in seconds by a researcher, relying on eye and memory, and checked by walking across a room and looking in similar boxes of photos of all ages and varying quality for a close match.’

If the high-resolution images online have made art more readily available, for now at least photography continues to fulfil a function that it has always carried out. The pre-eminence of the actual work of art is surely unassailable, though as museums search for new ways to draw visitors, digital projects are likely to become ever more common. Where a radical transformation seems likely is in the use of machine vision as a tool to make new and unexpected connections between images. But before then the mundane, and largely manual task of digitising collections has to happen, and that, it seems, can’t be rushed.

From the October 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Treister’s tarot offers humanity a new toolbox